Makerbot mp03955 desktop digitizer 3d scanner

31 comments

Blood both liquid and seven elements

To renew a subscription please login first. It was the Stuarts who introduced the Irish to the slave trade. Charles II returned to the throne in at a time when it was becoming clear that sugar plantations were as valuable as gold-mines.

Irish names can be found among those working for the RAC. Among the most successful was William Ronan, who worked in West Africa for a decade — A Catholic Irishman, he rose to become the chairman of the committee of merchants at Cape Castle in present-day Ghana, his career apparently unhindered by the ascent of William of Orange.

In the seventeenth century Europeans saw slaving as respectable and desirable. It was conveniently accepted that Africans sold into slavery by their rulers were prisoners of war, who would otherwise have been slaughtered.

Thus export to the Americas offered them prolonged life in a Christian society. It was a century later, when public sensitivities began to change, that such attitudes to the slave trade were called into question. Nantes In Europe the connection between the Stuarts and Irish slave-traders was not lost with the throne.

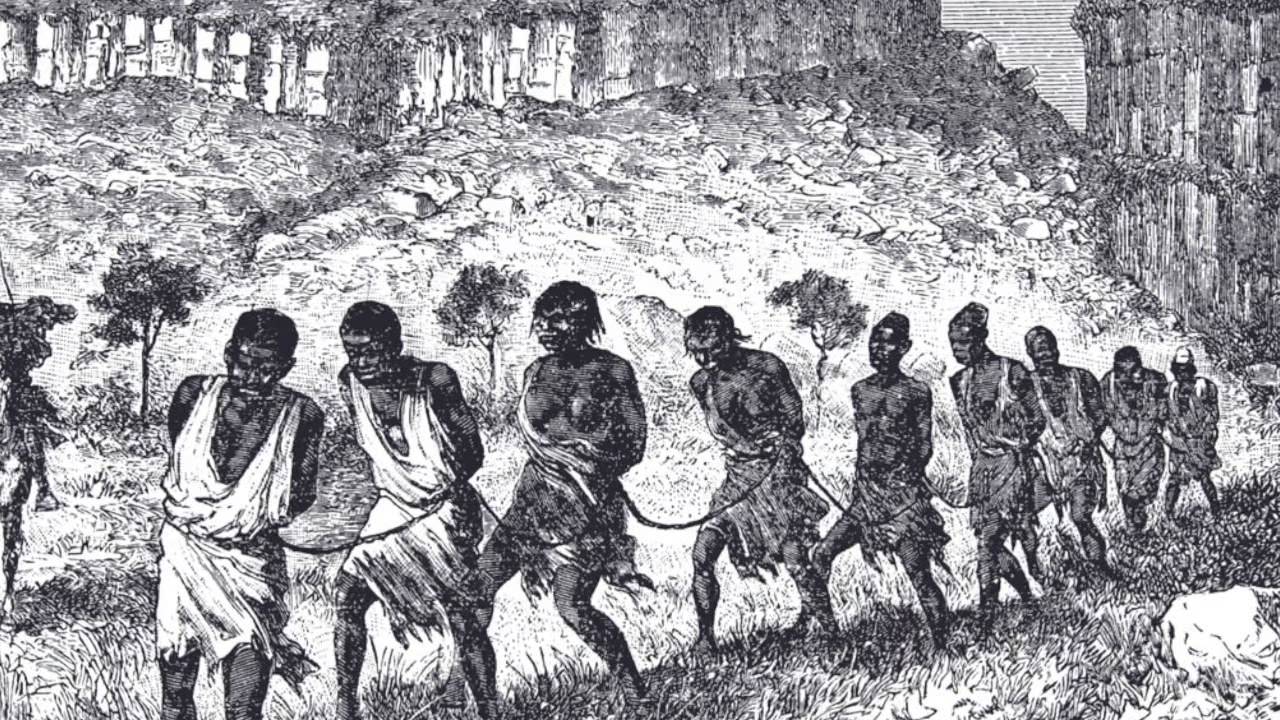

Antoine Walsh could afford this political gesture because of the wealth he had made from the slave trade. Prolonged loading in Africa was the most hazardous part of the operation. The climate was unhealthy and the slaves, still within sight of the shore, were at their most furiously desperate.

Fear of revolt, which could be mitigated for the armateur by insurance cover, was rife among captains and crew. By the early s Antoine Walsh had shifted from slave-ship captain to slave-merchant. He never actually experienced revolt himself but his relatives and employees did. At this point Barnaby Shiell, with five armed sailors, fired on the Africans.

In the ensuing slaughter two crew and 40 slaves were killed. The result in commercial terms was the destruction of one-sixth of the cargo. Undeterred by this set-back, Captain J. Shaughnessy determinedly pursued his professional objectives, remaining at Whydah until he was finally able to sail with Africans for St Domingue and Martinique.

After the Jacobite defeat, Walsh turned back to slaving, and immediately one of his ships became the scene of a slave revolt. As the ship got ready to sail, six women, one with a child at the breast, threw themselves overboard and drowned. A month later, off the island of San Thome, the remaining slaves rose and killed the captain and two sailors. The crew threatened to resort to firearms but the Africans took no notice and the result was 36 dead.

By the eighteenth century Africans were accustomed to guns. The desire to possess them was one of the factors fuelling the trade and bringing about political change as states grew stronger or weaker according to their access to firepower. But those Africans delivered to the ships as slaves were devoid of weapons.

For an experienced slave-trader it was a familiar professional set-back. As far as Walsh was concerned, the real danger to his ambitions had surfaced within Nantes itself. Walsh had risen as an independent himself but now wanted to prevent the rise of other independents. His financial innovations in France were to be underpinned by novel arrangements in Africa.

The company would have three large ships stocked with trade goods permanently stationed off the Angolan coast. Five smaller ships would make an annual Atlantic crossing to St Domingue, where they would deliver their cargo into a fortified slave-camp. After launching 40 voyages, his career as an armateur had come to an end. Over the years Antoine Walsh had purchased over 12, Africans for export across the Atlantic, though not all of them had reached the Americas.

No other family from the Irish community in Nantes could claim anything approaching such a score, although two others, the Rirdans and the Roches, emerged as significant armateurs. Cork, sent out eleven expeditions during the years —49, purchasing just over 3, slaves. Between and the Roche family their roots in Limerick, where they possessed marriage connections with Arthurs and Suttons organised a similar number. This opened up the slave trade to individual British merchants, while banning Irish ports from launching direct voyages to Africa.

Their success over several generations was marked by their move into Queen Square, where they lived in an elegant new building looking out on a handsome statue of William III. By the s they had disappeared, to be replaced by John Coghlan and James Connor. In s Liverpool there were slave-merchants with Irish names: But the first four had all been born in that area; only Tuohy had arrived as a young man from Tralee.

From the s onwards he and his brother-in-law, Philip Nagle, captained ships to Africa. Though he gave up sailing to Africa himself after , he continued to despatch ships for slaves. The men mentioned above were professional survivors and successes.

In France and Britain many of those emerging as slave-merchants had begun life as captains in the trade. At least five captains died in Africa for every one who achieved the status of merchant.

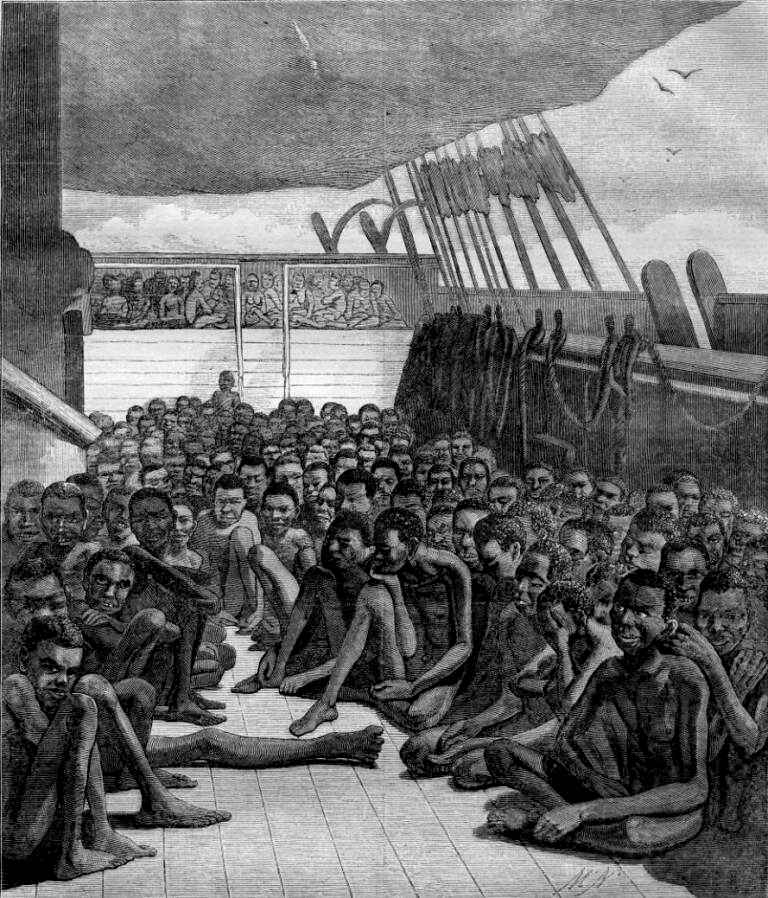

It began its climb to notoriety in , when the abolitionists produced a diagram of the vessel showing shackled slaves, arranged with mathematical precision, head to toe, layer upon layer, not an inch of space unused. Confronted by an enemy privateer near Barbados, he armed 50 of his cargo and successfully repelled the attack. The number of Scots and Manx captaining Liverpool slave-ships exceeded those from Ireland.

But among ordinary sailors the position was reversed and the Irish formed the most numerous non-English group—more than 12 per cent as against the Scots with 9. Already an evangelical, but still inhabiting a pre-anti-slavery world, he held services on board for the crew, never thinking of extending his religious ministrations to the Africans he was loading and shackling down below.

His papers record them as numbers, while his crew names reveal an Irish presence: Some of the Irish names presented Newton with greater difficulty. I hope this has been the first affair of the kind on board and I am determined to keep them quiet if possible. If anything happens to the woman I will impute it to him, for she was big with child. Her number is The crew themselves rarely wrote about their voyages. Two brothers from Ireland have left an account of such experiences, however.

Nicholas and Blaney Owen came from an impoverished gentry background. In at Banana Island, south of Sierra Leone, their ship was seized by locals, angry because a Dutch captain had recently removed some of their free men. At first the Africans held the crew captive but later allowed them to wander off. The brothers eventually found work with an African-born mulatto who had developed a trading post manned by his wives, children and slaves.

For commercial convenience, the Owens built themselves houses at separate points on the Sherbrow River. In Africa he felt that he had acquired something of the gentry lifestyle he had forfeited at home. But, as he very well understood, it was at the cost of staying there. But when he was ill it was a different matter. Shuddering with malaria, unable to supervise business, homesickness would strike.

As the journal survived, Blaney may also have done so. The tale of the Irish brothers, one dying in Africa, the other returning without having made his fortune, encapsulates the experience of most slave-ship crewmen. The West Indies Across the Atlantic, in the Caribbean, a group of second-generation Irish emigrants were making fortunes from buying and selling slaves. Since the seventeenth century the Irish had been settling in the Leewards, a string of physically varied and politically diverse islands.

Their presence on nearby Antigua and Nevis was also statistically significant, representing around a quarter of all whites. Slaves were arriving in huge numbers into the Leewards in the eighteenth century. A Cork man working as an overseer in Antigua in the s, and writing later to defend the trade, described the arrival of the Guinea ships with slaves dancing, gay, hung with glass beads, as if celebrating a festival.

On Montserrat, Skerrets, Ryans and Tuites busied themselves in inter-island trading, buying slaves from British ships and then re-exporting them, along with cargoes of provisions from Ireland. While the Danes possessed the capital and mercantile expertise necessary for running such a venture, they did not possess manpower eager or suitable for planting their new possession.

It was Nicholas Tuite who solved this problem for them, importing slaves and encouraging other Montserratians, supplemented by individuals from Ireland itself, to move there. Tuite himself now owned seven plantations there and was part-owner of seven others. Like Antoine Walsh, slave-trading and plantation-owning had made him the friend of kings. Every group in Ireland produced merchants who benefited from the slave trade and the expanding slave colonies.

All slave-trading voyages required minor investors. In the s the Presbyterian McCammons of Newry put money into at least one Liverpool voyage and actually ended up owning a slave. Almost four decades later their cousins James and Lambert Blair, following up West Indian connections, went out to St Eustatius, where they set up as agents, their main source of income derived by purchasing slaves for the Stevenson plantation.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century the Napoleonic wars brought Britain the Dutch territory of Demerara.

The Blairs, now with funds to invest, were quick to buy land in Demerara and stock it with slaves to develop sugar plantations. He thus claimed for more slaves and received more money than any other slave-owner in the British Empire. The eighteenth-century economies of Cork, Limerick and Belfast expanded on the back of salted and pickled provisions specially designed to survive high temperatures. Products grown on slave plantations, sugar in the Caribbean and tobacco from the North American colonies, poured into eighteenth-century Ireland.

Commercial interests throughout the island, and the parliament in Dublin, were vividly aware of how much wealth and revenue could be made from the imports. Behind her two armed and uniformed figures stand on guard while merchant ships approach at full sail. In the foreground, flanked by tobacco barrels, are three figures, kneeling before Hibernia to offer gifts. On the left an Irish woman holds out cloths, presumably a reference to the right of Ireland to freely export her textile production.

Beside her an American Indian offers an animal pelt. On the right a black slave, strong, sinewy and briefly draped, extends a neoclassical urn, its precious metal representing the untold wealth of Africa and America.

By Limerick and Belfast had drawn up and published detailed plans for the launching of slave-trade companies.